1920s

Armagh Apples

County Armagh is known as the ‘Apple blossom’ county or the ‘Orchard County it is definitely apple country, and todays its famous Bradley apples have been awarded with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status by the EU. This recognises the specific area which the product comes from protecting and promoting named regional food products that have a reputation or noted characteristics specific to that area.

Recognised for its distinctive taste and flavour, the Armagh Bramley apple is a culinary apple like no other. Traditionally grown and cared for in the region of Armagh, the area has a longstanding and historically significant link to the apple.

Generations of apple growers come largely from County Armagh and the surrounding areas. So impressive are the Bramley orchards of Armagh the county is celebrated as the ‘Orchard County of Ireland’.

About a third of the world’s supply of Bramley apples are grown in Ireland, largely in and around County Armagh. It is the only apple available today for the sole purpose of cooking. Its development since its humble beginnings in 1809 is impressive, the orchards of Armagh are now more than 90% Bramley by area.

County Armagh has been part of the apple growing family for generations; growers take pride in their ability to grow quality produce observing only the best in agricultural practices to achieve the finest cooking apples, which are used in both sweet and savoury dishes and drinks.

The Armagh Bramley is used in the trade by chefs, as well as by shoppers and families from the area who over the years have built up a collection of favourite recipes.

Useful Links

Dunluce Castle

Sitting on the headland of the North Antrim coast keeping silent watch over the sea is the imposing romantic ruin of Dunluce Castle. Once a stronghold of Anglo-Norman knights it became the power base of competing Ulster Scots clans. Home to a Plantation town it witnessed the ravages of the 1641 Rebellion and held the secret of Spanish Armada gold for centuries.

History of Dunluce Castle

The first castle at Dunluce was built in the 13th century by Richard de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster. However, the ruins left today are from the 16th and 17th centuries, when Dunluce became the seat of Clan McDonnell, who overthrew their rivals, the McQuillans, who were Lords of Route.

Around 1608, Randal McDonnell, 1st Earl of Antrim, built the town of Dunluce next to the castle. It was rediscovered in 2011, having been razed to the ground in 1641, and archaeological discoveries suggest a sophisticated piece of town planning around a grid system, as well as evidence of indoor toilets, which were extremely rare at the time.

The castle has its fair share of legends, including part of the kitchen collapsing into the sea, and a resident banshee, Maeve Roe, who tried to elope with her true love but drowned in the stormy seas lurking below.

Dunluce served as the seat of the Earls of Antrim until the family’s fortunes changed following the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. As money dwindled, the castle was left to ruin – parts of it fell into the sea, whilst other stones were scavenged as building materials. Nevertheless, the site was passed down over the centuries, until it came into the part ownership of Winston Churchill through his marriage to Clementine Hozier. He gave his share of the castle to the Northern Irish government in 1928.

Since then, Dunluce has been maintained by the state. It shot to fame as the seat of House Greyjoy, the castle of Pyke, in Game of Thrones.

Dunluce is a romantic ruin today. Sitting atop the craggy rocks, with the blue sea crashing below, it truly does feel like something straight out of a film set. On a grey or stormy day, you’ll be surprised that the castle has survived this long in such a precarious position. Allow an hour or two to fully explore the ruins and soak up some of the magic.

It’s worth trying to arrive early or late – Dunluce has become increasingly popular with tour groups, and when a coachload of people arrive, something of the atmosphere is lost. It’s particularly lovely in the late afternoon: try arriving 45 minutes before closing time to soak up the last of the dregs of sun and hit golden hour.

Getting to Dunluce Castle

Dunluce is just off the A2, about 4 miles east of Portrush. There’s somewhat limited parking nearby (blame the Game of Thrones tourism boom), so if you’re feeling keen, you can walk from Portrush itself – it’s about an hour along glorious coastal paths.

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

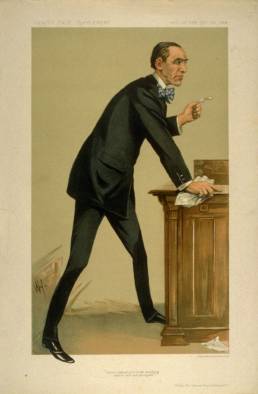

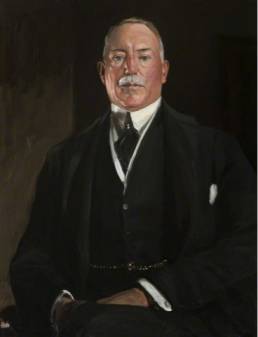

Edward Carson

Edward Carson, Lord Carson of Duncairn.

1854-1935

Edward Carson’s image is that of an intransigent unionist leader who helped raise the political temperature in Ireland and bring it to the brink of civil conflict. However, he himself felt a profound sense of unease about the measures then being taken by his supporters in Ulster.

Carson was born in Dublin, into a liberal professional middle class family and studied law at Trinity College. He was amongst the most successful lawyers of his generation. The reputation he acquired led to his election as Unionist MP for Trinity College (1892-1918), and to his becoming Solicitor-General for Ireland (1892), and for England (1900-05). Carson acted as Crown Prosecutor during the Irish land agitation, 1888-91, defended Queensberry in the first trial of Oscar Wilde (1895) and was involved in the ‘Winslow Boy’ case. In parliament his speech attacking the Second Home Rule Bill in 1893 was widely acclaimed; he had emerged by 1906 as one of the most prominent politicians in the United Kingdom.

In February 1910, Carson agreed to become leader of the Irish Unionist Parliamentary Party and in June 1911 accepted Craig’s invitation to lead the Ulster Unionists. He brought credibility and prestige to the movement. His objective throughout was to preserve the union between Britain and Ireland, believing it to be in the best interests of his fellow-countrymen; he was an Irish patriot, but not a nationalist. During the home rule crisis, 1912-14, he aimed to foment and use Ulster’s resistance as a means of blocking any granting of self-government to Ireland. Owing to his undoubted charisma, inspired oratory and unyielding image, he was hero-worshiped by unionists in the province of his adoption. Carson was deeply uneasy about the decision to establish an Ulster Volunteer Force and to run guns through Larne. However he accepted them as a means of applying additional pressure to the British government and so reaching the negotiated agreement he privately sought. By 1914, he had come to support Irish partition as a solution, fatalistically accepting that home rule was inevitable. By then his strategy had brought Ireland close to civil war.

Though Carson remained as unionist leader up to 1921, in wartime he spoke in favour of all-Ireland political institutions and structures, which lost him support in Ulster. Moreover, his energies were diverted into other areas. He played a significant role in the removal of Asquith as Prime Minister in 1916. During the conflict he also served in the British government, successively as Attorney General, First Lord of the Admiralty and in the War Cabinet. In 1919 he eagerly returned to his legal practice and he accepted a peerage in 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) was strongly criticised by him, but from a southern Irish unionist perspective. He died in 1935 and is buried in St. Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast. ‘Northern Ireland provided him with a tomb, but not a home.’

Lesson Plans

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

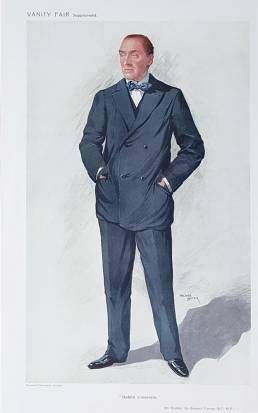

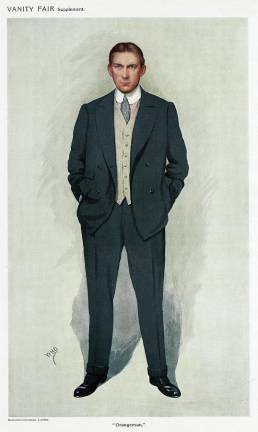

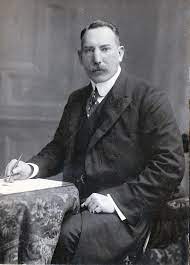

James Craig

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon.

1871-1940

James Craig is rightly regarded by Ulster Unionists as the founding father of the Northern Ireland state. More than any other leader, he mobilised the pre-war unionist resistance to home rule and then became the first premier of Northern Ireland, holding that office for almost twenty years.

Craig was born near Belfast, the son of a self-made millionaire whiskey distiller. He attended school in Scotland before working as a stockbroker and serving in the second Boer War. Entering parliament as a Unionist in 1906, representing East Down, 1906-18 and Mid-Down, 1918-21, he quickly established a reputation as a promising backbencher. He was the architect of Ulster unionist resistance to home rule, 1912-14. His contribution was not as an ideologue or charismatic leader; his strength lay in his organisational ability. He arranged for Edward Carson to act as unionist leader, its public face, whilst he masterminded the campaign of resistance; he stage-managed Covenant Day (28th September 1912), supported and helped organise the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and helped persuade colleagues of the need to import arms prior to the Larne gun-running. Throughout this his overriding concern was to keep Ulster within the Union. Unlike Carson by 1914 he had embraced partition with enthusiasm rather than resignation.

In wartime, Craig encouraged the UVF to enlist; he himself repeatedly failed his army medical. Between 1917-21, he held a succession of junior British government posts with distinction. He also helped influence the terms of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920. It was partly due to Craig that a six county territory for Northern Ireland was chosen, rather than the nine counties favoured by English ministers and some unionists. Though reluctant to abandon a promising ministerial career at Westminster, he accepted the premiership of the six counties in 1921, and remained in office until his death in November 1940.

Craig overcame the military and political opposition which the new state faced, especially from the IRA campaign of 1920-22. He withstood the British government’s efforts during the Treaty negotiations to subordinate Northern Ireland to a Dublin parliament. In addition, he sustained substantial unionist majorities in successive elections for the devolved parliament (1921, ‘25, ‘29, ‘33, ‘38) and secured his party’s domination of local government. But his successes were achieved at the price of a harsh security policy and the neglect of pressing problems. Craig made no sustained attempt to integrate the disaffected minority in the north and no energetic effort to halt or compensate for the decline of the regional industrial economy. Housing, health, and education provision were likewise neglected. Mainly because of declining health, Craig’s premiership was marked by his own increasing political disengagement and long absences from the province. In later years, he presided over the state in a casual, paternalistic manner. His ineffective wartime leadership, 1939-40 generated mounting criticism, even from within his own party. He died at home on 24th November 1940.

Lesson Plans

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3