Communication

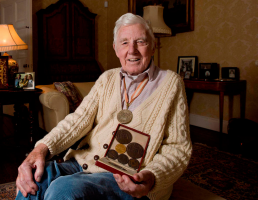

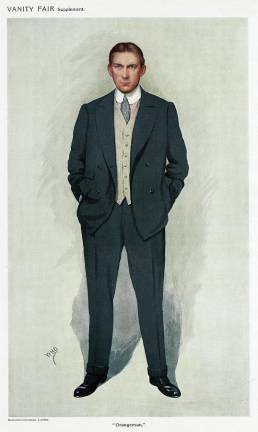

Robin Dixon, Lord Glentoran - Gold Olympic Medal

World class sportsman and Gold medal winning Olympian Robin Dixon, Lord Glentoran brought home Gold for Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1964

Major Thomas “Robin” Valerian Dixon, 3rd Baron Glentoran, CBE (born 21st April 1935) is a former British bobsledder and Northern Irish politician, known as Robin Dixon. He is a former Conservative Party Shadow Minister for the Olympics.

Dixon was educated at Eton and Grenoble in France. After university, he served with the Grenadier Guards from 1954 to 1966 including service in the Cyprus Emergency

In 1964, Dixon was granted leave from the army to participate in the 1964 Winter Olympics at Innsbruck, where he won the gold medal in the Two-man Bobsleigh as brakeman to Tony Nash and was awarded a MBE a year later. Nash and Dixon also won three medals in the two-man event at the FIBT World Championships with one gold (1965) and two bronzes (1963, 1966).

Dixon retained his sporting links throughout his life: he was President of the Jury at the 1976 Winter Olympics, set up the Ulster Games Foundation in 1983, and was appointed Chairman of the Northern Ireland Tall Ships Council in 1987. He has been President of the British Bobsleigh Association since 1987

By the time, Dixon had left the Army in 1966 with the rank of Major, he had also served with 3 Para and the SAS in the Cyprus and Borneo conflicts, and gone into business at home in Northern Ireland. “My family felt it was time I started contributing to the life of the province,” he explains.

He went on to work for Kodak in their public relations department and in 1971 joined the Northern Irish business, Redland Tile and Brick Ltd, which he built up into a multimillion-pound subsidiary of Redland plc and became Managing Director.

In 1983, he was appointed High Sheriff of Antrim.

Upon the 1995 death of his father, the 2nd Baron Glentoran, Dixon inherited his title, and he retired from business in 1998.

Dixon was Chairman of Positively Belfast from 1992 to 1996, Chairman of the “Growing a Green Economy” Committee from 1993 to 1995 and has been Shadow Minister for Northern Ireland, Shadow Minister for Sport and Shadow Minister for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. He is also a member of the British-Irish Parliamentary Body.

Lord Glentoran was one of 92 hereditary peers that remain in the House of Lords after the passing of the House of Lords Act 1999, and sat on the Conservative benches until his retirement from the House on 1 June 2018, travelling frequently from his family home, Drumadarragh House, near Ballyclare.

Dixon and his driver, Tony Nash, were inducted into the British Bobsleigh Hall of Fame as a result of their success. A curve at the St. Moritz-Celerina Olympic Bobrun is named for both Nash and Dixon. He was appointed a CBE in 1993 for services to Northern Ireland and Industry.

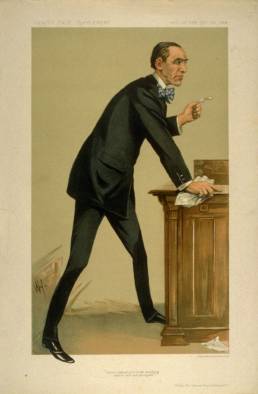

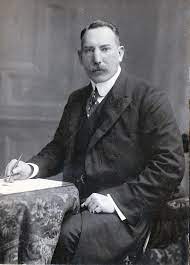

Edward Carson

Edward Carson, Lord Carson of Duncairn.

1854-1935

Edward Carson’s image is that of an intransigent unionist leader who helped raise the political temperature in Ireland and bring it to the brink of civil conflict. However, he himself felt a profound sense of unease about the measures then being taken by his supporters in Ulster.

Carson was born in Dublin, into a liberal professional middle class family and studied law at Trinity College. He was amongst the most successful lawyers of his generation. The reputation he acquired led to his election as Unionist MP for Trinity College (1892-1918), and to his becoming Solicitor-General for Ireland (1892), and for England (1900-05). Carson acted as Crown Prosecutor during the Irish land agitation, 1888-91, defended Queensberry in the first trial of Oscar Wilde (1895) and was involved in the ‘Winslow Boy’ case. In parliament his speech attacking the Second Home Rule Bill in 1893 was widely acclaimed; he had emerged by 1906 as one of the most prominent politicians in the United Kingdom.

In February 1910, Carson agreed to become leader of the Irish Unionist Parliamentary Party and in June 1911 accepted Craig’s invitation to lead the Ulster Unionists. He brought credibility and prestige to the movement. His objective throughout was to preserve the union between Britain and Ireland, believing it to be in the best interests of his fellow-countrymen; he was an Irish patriot, but not a nationalist. During the home rule crisis, 1912-14, he aimed to foment and use Ulster’s resistance as a means of blocking any granting of self-government to Ireland. Owing to his undoubted charisma, inspired oratory and unyielding image, he was hero-worshiped by unionists in the province of his adoption. Carson was deeply uneasy about the decision to establish an Ulster Volunteer Force and to run guns through Larne. However he accepted them as a means of applying additional pressure to the British government and so reaching the negotiated agreement he privately sought. By 1914, he had come to support Irish partition as a solution, fatalistically accepting that home rule was inevitable. By then his strategy had brought Ireland close to civil war.

Though Carson remained as unionist leader up to 1921, in wartime he spoke in favour of all-Ireland political institutions and structures, which lost him support in Ulster. Moreover, his energies were diverted into other areas. He played a significant role in the removal of Asquith as Prime Minister in 1916. During the conflict he also served in the British government, successively as Attorney General, First Lord of the Admiralty and in the War Cabinet. In 1919 he eagerly returned to his legal practice and he accepted a peerage in 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) was strongly criticised by him, but from a southern Irish unionist perspective. He died in 1935 and is buried in St. Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast. ‘Northern Ireland provided him with a tomb, but not a home.’

Lesson Plans

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

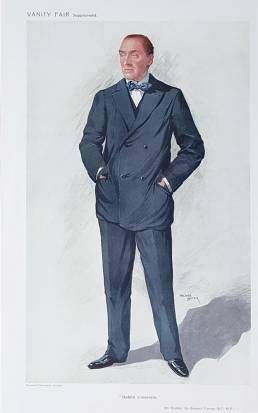

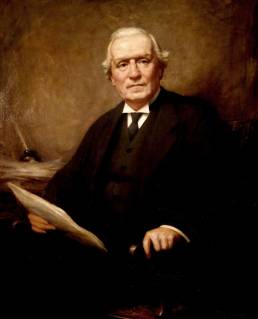

James Craig

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon.

1871-1940

James Craig is rightly regarded by Ulster Unionists as the founding father of the Northern Ireland state. More than any other leader, he mobilised the pre-war unionist resistance to home rule and then became the first premier of Northern Ireland, holding that office for almost twenty years.

Craig was born near Belfast, the son of a self-made millionaire whiskey distiller. He attended school in Scotland before working as a stockbroker and serving in the second Boer War. Entering parliament as a Unionist in 1906, representing East Down, 1906-18 and Mid-Down, 1918-21, he quickly established a reputation as a promising backbencher. He was the architect of Ulster unionist resistance to home rule, 1912-14. His contribution was not as an ideologue or charismatic leader; his strength lay in his organisational ability. He arranged for Edward Carson to act as unionist leader, its public face, whilst he masterminded the campaign of resistance; he stage-managed Covenant Day (28th September 1912), supported and helped organise the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and helped persuade colleagues of the need to import arms prior to the Larne gun-running. Throughout this his overriding concern was to keep Ulster within the Union. Unlike Carson by 1914 he had embraced partition with enthusiasm rather than resignation.

In wartime, Craig encouraged the UVF to enlist; he himself repeatedly failed his army medical. Between 1917-21, he held a succession of junior British government posts with distinction. He also helped influence the terms of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920. It was partly due to Craig that a six county territory for Northern Ireland was chosen, rather than the nine counties favoured by English ministers and some unionists. Though reluctant to abandon a promising ministerial career at Westminster, he accepted the premiership of the six counties in 1921, and remained in office until his death in November 1940.

Craig overcame the military and political opposition which the new state faced, especially from the IRA campaign of 1920-22. He withstood the British government’s efforts during the Treaty negotiations to subordinate Northern Ireland to a Dublin parliament. In addition, he sustained substantial unionist majorities in successive elections for the devolved parliament (1921, ‘25, ‘29, ‘33, ‘38) and secured his party’s domination of local government. But his successes were achieved at the price of a harsh security policy and the neglect of pressing problems. Craig made no sustained attempt to integrate the disaffected minority in the north and no energetic effort to halt or compensate for the decline of the regional industrial economy. Housing, health, and education provision were likewise neglected. Mainly because of declining health, Craig’s premiership was marked by his own increasing political disengagement and long absences from the province. In later years, he presided over the state in a casual, paternalistic manner. His ineffective wartime leadership, 1939-40 generated mounting criticism, even from within his own party. He died at home on 24th November 1940.

Lesson Plans

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

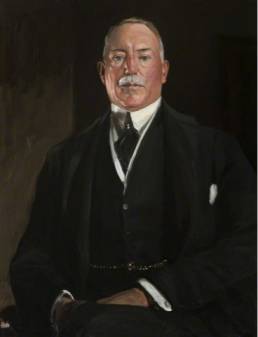

Herbert Asquith

Herbert Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

1852-1928

Herbert Asquith is chiefly remembered as the Prime Minister who passed the ‘liberal reforms’, which laid the foundations of the welfare state. However, he proved to be an ineffective leader in wartime; arguably his failings then were foreshadowed by his mishandling of the Irish question before the conflict began.

Asquith was brought up in Huddersfield where his family had interests in the woollen trade. After gaining a scholarship to Oxford he qualified as a barrister before winning a safe Liberal seat, East Fife, which he held from1885-1918. He was a formidable parliamentarian; his first ministerial post was Home Secretary under Gladstone, 1892-95. Asquith was a highly successful Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1905-08, and became Prime Minister on the retirement of Campbell-Bannerman in 1908. During his premiership he presided over a highly talented cabinet, 1908-14, which was responsible for the ‘liberal reforms’ and for legislation in 1911 reducing the powers of the Lords.

After narrowly winning two General Elections in 1910, his government, dependent on Irish Parliamentary Party support, introduced the Third Home Rule Bill in April 1912. This was based closely on Gladstone’s bills of 1886 and 1893; it would have granted Ireland limited self-government, creating a parliament in Dublin with 32-county jurisdiction. Politically, the most significant weakness of the measure was its failure to cater for the specific interests of the Ulster unionists, and they succeeded in mobilizing effective opposition to it, attracting much influential support in Britain. Beset by other problems – votes for women, industrial unrest – Asquith is criticised for adopting a ‘wait and see’ strategy in response. After introducing the measure, controversially he took no further initiative until March 1914. Meanwhile, between 1912 -14, attitudes in Ireland hardened and a crisis developed, with the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force and Irish Volunteer Force and gun-running into Larne and Howth. His belated attempts at finding a compromise solution, March-July 1914, failed hopelessly. The likelihood of civil conflict was only averted by the outbreak of war in Europe, when both the nationalist and unionist leadership agreed to postpone a settlement of the Irish question until after hostilities had ceased. This did not prove possible however. After the Easter Rising, Asquith exercised some influence to prevent the execution of more of the rebels. At the same time, he initiated negotiations with the intention of immediately granting home rule to Ireland but these ended without agreement.

Asquith proved to be an ineffective British wartime leader, his party split and he resigned from the premiership in 1916; he never again held political office. He died in 1928.

Lesson Plans

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3

Useful Links

Link 1

Link 2

Link 3